Optimize Your Clinic Workflow: New and Improved Calendar Features on Embodia

Discover Embodia’s latest clinic scheduling update, including a collapsible sidebar, full-screen calendar view, and powerful EMR scheduling tools. Learn how Embodia’s practice management calendar helps healthcare clinics schedule smarter with a new full-screen view and advanced features.

Is Concussion Rehab Really as Complex as It Seems?

Discover practical, evidence-based strategies for physiotherapists managing concussion in private practice. Learn how to build confidence, navigate evolving guidelines, assess key impairments, and collaborate effectively within an interdisciplinary team to support patients with persistent post-concussion symptoms.

Are Post-Traumatic Headaches and Concussions the Same Thing?

Learn how post-traumatic headaches differ from concussions, the types of trauma-related headaches, and why rest may not always be the best treatment.

Evolving Pelvic Health Care: Why a Biopsychosocial-Spiritual Approach Is Essential—And How to Integrate It Into Practice

Discover why nociplastic pain and modern pain science are reshaping pelvic health practice. This blog highlights insights from Carolyn Vandyken and invites you to her upcoming webinar on BPSS assessment and treatment.

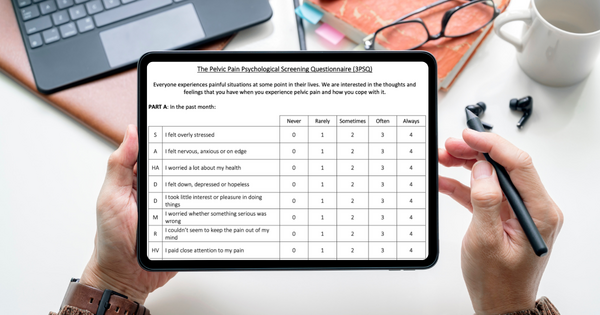

Embracing a Biopsychosocial Approach in Pelvic Health: Introducing the 3PSQ and Fre-PAQ

Explore a holistic, patient‑centered biopsychosocial approach to pelvic health — featuring two new tools for screening: the 3PSQ for psychological distress and the Fre‑PAQ for sensory‑motor dysregulation.

How to Turn Down the Volume on Persistent Pain A Practical, Neuroscience-Informed Approach for Physiotherapists

Learn how to help patients understand and manage persistent pain by turning down its volume through brain-based education and whole-person strategies.

Unlocking Movement Potential: Feldenkrais Method for Better Motor Learning

Integrate neuroscience and mindful movement. Discover how Feldenkrais principles elevate motor learning and rehabilitation in physiotherapy.

Embodia Is Now a CEU-Approved Provider in the U.S.

Embodia is an approved CEU provider for U.S. PTs and PTAs. Learn how to find CEU-approved courses & why adding your CEU jurisdiction to your profile matters.

Stop Throwing Spaghetti at Brick Walls! Why Pain Education Matters

Discover how better communication enhances patient outcomes. Learn practical pain education skills with Mike Stewart’s course on Embodia.

Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy: A Clinician’s Guide to Evidence-Based Assessment and Rehabilitation

The Clinical Practice Guideline by Dr. Dubé et al. offers an evidence-based approach for managing rotator cuff tendinopathy. Explore key takeaways in our blog.

Launch Your Own Custom-Branded Clinic App with Embodia

Elevate patient engagement with a customizable Progressive Web App (PWA) — now available to Tier 3: Practice Management clinics on Embodia.

How to Build and Grow a Successful Niche Physiotherapy Business

Whether you're just starting your own physiotherapy business, or honing your existing one, check out these five steps to achieve business growth and success.